Who Cares for the Caregivers?

According to Canada’s 2021 census, more than 861,000 people were aged 85 and older. By 2046, that number is projected to triple, reaching 2.5 million. Canada is clearly following in the footsteps of countries like Japan, entering the ranks of a “super-aged society.” Among those aged 85 and above, approximately 75% still live at home, with primary caregiving often falling to family members. It’s estimated that over 8 million Canadians currently serve as unpaid caregivers.

Within the Chinese community, caregiving is further complicated by language and cultural barriers. In June of this year, a memoir written by a caregiver was published in Taiwan, recounting the author’s experience of bringing her stroke-stricken father, mother with dementia, and brother with mental illness from Toronto back to Hong Kong to care for them. Our publication interviewed the author overseas. We also spoke with an 80-year-old daughter in Toronto who single-handedly cares for her 106-year-old mother at home.

Some return. Some stay. How do caregivers continue walking this path?

The author, veteran Hong Kong journalist Vivian Tam, immigrated to Canada with her family in the 1990s and graduated from the University of Toronto. Over twenty years ago, she returned to Hong Kong to pursue a journalism career and now teaches at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Yet for more than two decades, each visit back to Canada meant stepping into the role of the youngest daughter at home. As her parents aged, she became the primary caregiver for three family members. In an interview with our publication, she candidly admitted: “I often broke down.”

From both Hong Kong and Chinese Canadian perspectives, Vivian’s family represents a stable middle-class household—one that followed the post-war trajectory many Hong Kongers took to become social elites. Her parents worked hard to gain admission to public secondary schools, entered government service as civil servants, and retired with long-term pensions. Both children attended prestigious secondary schools in Hong Kong, earning top marks in public exams (each scoring six A’s), and were admitted to university. In the 1990s, the parents retired and immigrated to Toronto, settling into a spacious 3,000-square-foot home while the children continued their studies.

Vivian has worked as a journalist

in Hong Kong for many years

Vivian writes in her book:

“My brother refused to see a doctor, so only my dad went to the clinic to pick up medication. He had poor self-care—he wouldn’t bathe or brush his teeth for days, had long hair, didn’t shave, and his sleep schedule was completely reversed. He didn’t acknowledge his illness and stayed in his room for over a month, listening to music and making art. Even at 45, he was still wondering whether to return to university. During that time, he was completely isolated from society. Sometimes, under the influence of medication, he would become irritable and damage doors and windows in the house.”

Her parents, unable to cope, became his caregivers—using their own methods to care for him in isolation. Eventually, both developed health issues. Her mother showed signs of dementia but avoided medical help, and her father suffered a stroke during the pandemic. The family collapsed, and Vivian returned from Hong Kong to pick up the pieces.

“We had money, were financially stable, well-educated, and our parents weren’t bad to us. I came back wanting to solve the problems, but those few months shocked me. I felt that my father, mother, and brother’s behavior was completely beyond my imagination. Is this what aging and illness do? Their reactions were so exaggerated—it was like they had lost all rationality.”

Vivian once imagined herself as the dutiful daughter returning home to save her family. But after her father was discharged from the hospital, she realized they couldn’t manage on their own. From phone calls to daily routines and medical follow-ups, they were incapable of self-care. She couldn’t just leave after her vacation ended. The only viable solution was to bring them back to Hong Kong, where she could take full responsibility.

“I never thought about quitting my job to come back. I don’t think my parents would want me to quit either. I really love my job—it gives me satisfaction, income, and a sense of identity. I’ve seen a middle-aged woman quit her job to care for her family. She felt she had sacrificed a lot, and when caregiving became unpleasant, she felt even more aggrieved, believing her efforts weren’t appreciated. That made the relationships even more strained.”

“Canada emphasizes human rights—if a patient is unwilling, they cannot be forced into treatment. My brother refused medical care but wasn’t disturbing anyone, so he lived in that large house for over twenty years, and no one knew how severe his condition was.

As for the elderly, I know some people are adamantly against entering nursing homes. Their children struggle—constantly driving to deliver meals, managing incontinence at home. Canada doesn’t have live-in domestic helpers, which makes home care extremely difficult.

People think I was being radical by bringing them back to Hong Kong, but after 30 years of unresolved issues, could you really choose to stay in Canada? If my family knew how to navigate the system, things wouldn’t be like this. If my brother were willing to seek treatment and live independently, and my parents were open to entering a care facility, I could have peacefully returned to Hong Kong.”

Her father, however, rejected the plan. He refused to return to Hong Kong or enter a nursing home, insisting he would rather die in their 3,000-square-foot house. This deeply upset Vivian. She believes the hardest part of caregiving isn’t the physical or emotional labor—it’s reaching consensus with those being cared for.

“The hardest part isn’t the caregiving tasks—it’s when they don’t agree with you. That moment is terrifying.

As a daughter, I wanted to offer them a choice—to bring them back to Hong Kong and care for them as best I could. But their reaction was unanimous. They all disliked the idea and ganged up to scold me. I had to spend so much energy convincing them.

You could take a passive stance and say this responsibility isn’t yours, but I couldn’t accept that. Yet once you commit to bringing them back to Hong Kong, it’s as if you’re responsible for everything that happens afterward. That pressure is immense.

Why didn’t they plan ahead to deal with what’s happening now? Why is it that in the face of aging and illness, I’m the only one left to handle it?”

Even before returning to Hong Kong, Vivian had already been suffering under the weight of caregiving stress and required psychological therapy.

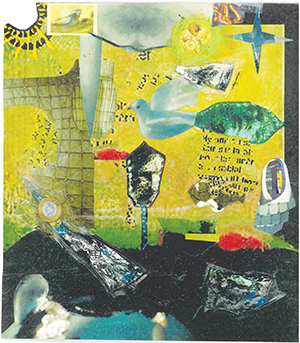

Award-winning piece by Vivian’s brother:

a sleeping figure marked with

a Toronto transit token,

symbolizing departure.

Vivian had originally planned to end her book Locked Home there, believing the solution she offered had truly “delivered results.” But something unexpected happened. After returning to Hong Kong, she invited visual artist Pak Sheung-chuen (白雙全) to analyze her brother’s decades of artwork. His pieces were entered into an art competition organized by Pak, and her brother was selected as one of the top ten finalists. Four of his works were exhibited at Art Basel in 2025, where he was invited to receive an award and deliver a speech.

Vivian added this chapter just before the manuscript deadline.

“I never wrote this book with any calculations in mind—I simply wanted to document our family’s journey. My brother’s award came about because I was writing the book and wanted to understand his work more deeply, which led me to Pak Sheung-chuen. His recognition means a great deal to our whole family.

My brother’s life has left a mark—it wasn’t just a fleeting presence. He existed in this world and deserves to be acknowledged, don’t you think? Our parents were proud of him too.

This turning point saved our entire family. That’s why I see Art Basel as a miracle—something beyond human control or effort.

Walking this path, I often felt pain, injustice, and loneliness. But in the end, something happened that exceeded all expectations, as if to tell me: your belief was right.”

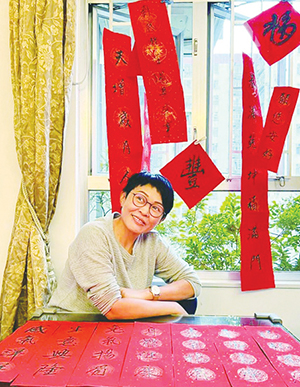

Vivian and her father pictured with

Spring Couplets they wrote upon

returning to Hong Kong

As for Vivian herself, she says she’s in a good place—going to the gym daily, cooking her own meals and soups, and building physical strength to better support her father. The role of the “resentful youngest daughter at home” has completely faded.

“I feel very calm now. There’s a genuine sense of peace inside me—unlike before, when I was filled with guilt, anger, frustration, and grievance.

As a caregiver, if you can’t take care of yourself and you’re falling apart, it’s not good for you or the person you’re caring for.

In the process of caregiving, we must try not to lose ourselves. The person being cared for may have many complaints and often vents on those closest to them, emotionally manipulating us—Chinese families are especially good at this.”

She continues:

“Many caregivers end up doubting themselves. I’ve felt that too—thinking I couldn’t handle it, being scolded by the person I was caring for, unable to see any hope ahead.

I even thought about tragic outcomes within the family.

Now that things have settled, the three of them each have their own lives. Looking back, I realize those thoughts were actually symptoms of depression. That’s why caregivers must affirm their own worth—and seek psychological support.” Shirley Chan

Shirley Chan